Pelvic Vasculature & Nerves; Walls

The major nerves and blood vessels of the pelvis course along its posterolateral walls in an extraperitoneal position (G11 3.5, 3.19, 3.24, 3.26, Tables 3.3 [pp. 212-213], 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.11, 3.12, 3.20, 3.27A, 3,39A; N257, 260, 378-380, 382-383, 390, 392, 487). In general the nerves lie peripheral, or lateral, to the vessels.

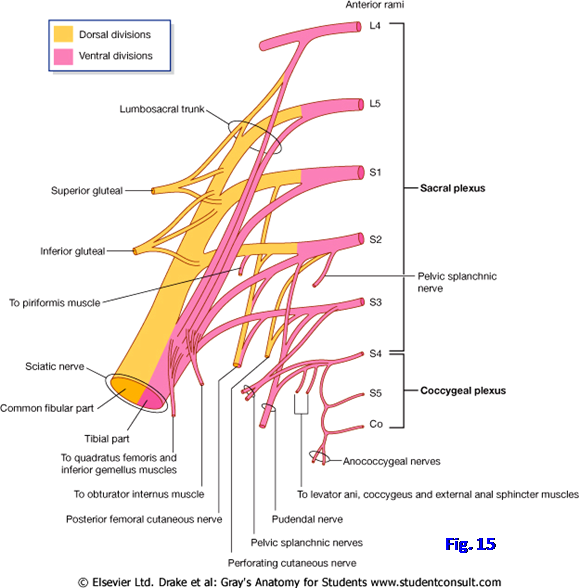

The pelvic nerves consist mainly of the sacral plexus and coccygeal plexus and the pelvic portion of the autonomic nervous system (Fig. 15; G11 3.24, 3.26, Table 3.4 [p. 223]; G12 3.11, 3.12, Table 3.3 [p. 207]; N390, 392, 485, 487). The sacral plexus is formed by the anterior rami of spinal nerves L4-S3 anterior to the piriformis muscle. The anterior rami of S1-S3 exit the pelvic sacral foramina and are joined by the lumbosacral trunk from L4-5 descending over the ala of the sacrum. Each anterior ramus receives a gray communicating ramus from the sacral sympathetic trunk carrying postganglionic sympathetic fibers to be distributed to the lower extremity (G11 3.25A; G12 3.12, Table 3.6 [p. 230]; N390).

The somatic nerves of the sacral plexus converge toward the greater sciatic foramen, where most leave the pelvic cavity to enter the gluteal region (Fig. 16; G11 3.5, 3.24, 3.25A, 3.26; G12 3.11, 3.12, 3.27A, Table 3.3 [p. 207]; N260, 319, 485, 487). These nerves were studied in the gluteal region during an earlier dissection. One branch of the sacral plexus, the pudendal nerve, briefly traverses the gluteal region to enter the perineum via the lesser sciatic foramen (G11 3.25B; G12 3.31B, 3.55B; N390, 391). The pudendal nerve is the major nerve supply of the perineum and the chief sensory nerve of the external genitalia.

The branches of the sacral plexus are the superior gluteal, inferior gluteal, sciatic, posterior femoral cutaneous, and pudendal nerves, along with the nerve to the obturator internus and the nerve to quadratus femoris (Fig. 15). Their peripheral distribution was studied with the lower extremity. We will now briefly consider the origin of the larger nerves of the plexus.

The anterior rami of L4-S3 divide into anterior and posterior divisions (Fig. 15), which in general are destined for posterior (flexor) and anterior (extensor) regions of the lower extremity, respectively. This is the reverse of the situation in the upper extremity, where anterior divisions of the brachial plexus supply anterior (flexor) compartments of the extremity and posterior divisions innervate posterior (extensor) compartments. The pattern of innervation of the upper and lower extremities differs because the upper extremity rotates 90° laterally during development while the lower extremity rotates 90° medially.The posterior divisions of L4-S1 form the superior gluteal nerve (Fig. 15; G11 3.24, 5.25, Tables 3.4 [p. 223], 5.6 [p. 374]; G12 3.12, 5.3B, 5.27A, Tables 3.3 [p. 207], 5.6 [p. 392]; N485, 487, 490), which exits the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle to supply the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae. The other branches of the sacral plexus exit the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. The posterior divisions of L5-S2 form the inferior gluteal nerve, which supplies the gluteus maximus.

The large sciatic nerve is really two nerves bound together by the connective tissue epineurium (Fig. 15; G11 3.24, 3.26, 5.25, Tables 3.4 [p. 223], 5.6 [p. 374]; G12 3.12, 5.26A, Tables 3.3 [p. 207], 5.6 [p. 392]; N485, 487, 490). The common fibular division of the sciatic nerve (common fibular nerve) is formed by the posterior divisions of L4-S2. It supplies the short head of the biceps femoris and muscles of the lateral and anterior compartments of the leg and dorsum of the foot. The tibial division of the sciatic nerve (tibial nerve) is formed by the anterior divisions of L4-S3. It supplies the hamstring muscles of the thigh and muscles of the posterior compartment of the leg and the sole of the foot. Since the sciatic nerve innervates the muscles of the posterior thigh and all of the muscles below the knee, its involvement by a pelvic tumor or other pathology results in major functional loss. An anatomical variation of potential clinical significance is that the common fibular nerve may pass above or through the piriformis muscle and be compressed by it (one possible cause of piriformis syndrome; see http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/308798-overview#showall ) (G11 5.26B; G12 5.28B).

Like the sciatic nerve, the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve is formed by fibers from both anterior and posterior divisions of the sacral plexus. It arises from S1-3 to supply the skin of the inferior gluteal region, posterior thigh, and proximal leg. Its perineal branch helps to innervate the scrotum or labium majus (N391, 393, 491).

The anterior divisions of S2-4 join to form the pudendal nerve (Fig. 15; G11 3.24, 3.25B, 3.50B, 5.24; G12 3.12, 3.55B, 5.26A, Table 3.3 [p. 207]; N391, 485, 487, 491). It exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen, curves around the ischial spine or beginning of the sacrospinous ligament, and enters the lesser sciatic foramen (G12 3.55B). The pudendal nerve is the major motor and sensory nerve of the perineum and will be studied in detail with that region in the next lab.

Two smaller nerves that arise from the anterior divisions of the sacral plexus are the nerve to the quadratus femoris and the nerve to the obturator internus (G11 5.25, Table 5.6 [p. 374]; G12 5.27A, Table 5.6 [p. 392]; N487, 491). The nerve to the quadratus femoris is formed from L4-S1 and also innervates the inferior gemellus muscle. The nerve to the obturator internus is formed by L5-S2 and also supplies the superior gemellus. This nerve follows the pudendal nerve around the ischial spine and into the lesser sciatic foramen to enter the obturator internus muscle.

The coccygeal plexus is formed by the anterior rami of S4, S5, and the coccygeal nerve (Co1) (Fig. 15; G11 3.24; G12 3.12; N 485, 487). It is a small group of nerves on the pelvic surface of the coccygeus muscle, which it innervates. The coccygeal plexus helps innervate the levator ani and sends the cutaneous anococcygeal nerves through the anococcygeal ligament to supply a small area of skin between the anus and tip of the coccyx.

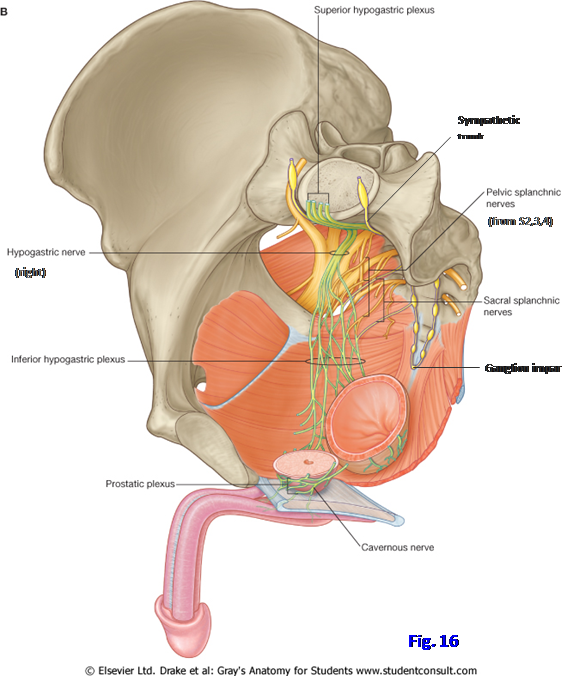

Pelvic autonomic innervation includes both sympathetic and parasympathetic components. The sacral sympathetic trunks are the inferior continuations of the lumbar sympathetic trunks as they cross the pelvic brim (Fig. 16; G11 3.23, 3.24, 3.25A, 3.26; G12 2.76, 2.77, 3.12, 3.31A,; N260, 297, 319, 392). The sacral sympathetic trunks descend medial to the anterior sacral foramina and converge to fuse in a small terminal ganglion, the ganglion impar, anterior to the coccyx. Each sacral sympathetic trunk consists predominantly of descending preganglionic sympathetic fibers from the intermediolateral cell column (IMLCC) of upper lumbar segments (L1-2) of the spinal cord. The preganglionic sympathetic fibers synapse in sacral sympathetic ganglia and the ganglia send gray rami communicantes to sacral spinal nerves to provide postganglionic sympathetic fibers to the smooth muscle and glands of the lower extremity.

Pelvic organs are innervated by visceral nerves from the inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexuses (Fig. 16; G11. 3.11, 3.23, 3.25; G12 2.76, 2.77, 3.31A, 3.41C, Table 3.6 [p. 230]; N389, 390, 392, 394). The inferior hypogastric plexuses are situated along the pelvic walls lateral to the rectum, the urinary bladder, and in the female the cervix of the uterus. They form sub-plexuses associated with pelvic viscera. These include right and left rectal and vesical plexuses in both sexes, prostatic plexuses in the male, and uterovaginal plexuses in the female. From the prostatic plexuses in the male cavernous nerves penetrate the pelvic floor to reach erectile tissues of the penis (G11 3.23A; G12 3.31B; N390). Corresponding nerves to erectile tissues in the female probably arise from the uterovaginal plexuses.

The inferior hypogastric plexuses consist of sympathetic fibers, parasympathetic fibers, and general visceral afferent fibers. Each of the contributions will now be discussed separately. (A more detailed discussion of abdominopelvic autonomic innervation can be found on pages 1041-1047 in Standring, Susan (Ed.) 2008 Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 40E, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.)

The more important route by which sympathetic nerve fibers reach pelvic viscera is via the hypogastric plexuses. The superior hypogastric plexus is the continuation of the intermesenteric (aortic) plexus of the abdomen (Fig. 16; G11 2.76, 2.78, 3.23, 3.25A, 3.37B; G12 2.76, 2.77, 2.79, 3.31A; N297, 389, 390, 392). The superior hypogastric plexus lies anterior to, and continues just below, the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta. Right and left hypogastric nerves descend from the superior hypogastric plexus into the pelvis, connecting it to the right and left inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexuses, respectively. The hypogastric nerves comprise mainly postganglionic sympathetic fibers with some descending from cell bodies in abdominal prevertebral ganglia and others arriving via the third and fourth lumbar splanchnic nerves.

Small branches from the sacral sympathetic ganglia (sacral splanchnic nerves) also contribute to the inferior hypogastric plexuses (G11 3.23B, 3.36B, 3.50B; G12 2.76, 2.77, 3.31B; N392, 397). There is some controversy as to whether the sacral splanchnic nerves are pre- or postganglionic sympathetic fibers, but the majority of fibers likely are postganglionic fibers from nerve cell bodies within sympathetic chain ganglia.

The parasympathetic contribution to the inferior hypogastric plexuses come from the pelvic splanchnic nerves (Fig. 16; G11 3.11, 3.25A, 3.36B, 3.39A, 3.50; G12 3.31A-B, 3.42, 3.43B-C; N390, 392, 395-397). These are preganglionic parasympathetic fibers from cell bodies in the sacral parasympathetic nuclei of spinal cord segments S2-4. The pelvic splanchnic nerves branch from the anterior rami of S2-4 to enter the inferior hypogastric plexuses. Some of the parasympathetic fibers are distributed to pelvic organs through branches of the inferior hypogastric plexuses. Other parasympathetic fibers ascend through the hypogastric nerves to innervate the colon beginning just proximal to the left colic flexure, where innervation of the digestive tract from the vagus nerves ends.

Summary of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of pelvic organs: In general, the sympathetic nerve fibers of the pelvis innervate the smooth muscle of blood vessels as well as smooth muscle of the internal urethral sphincter, internal anal sphincter, and the ductus deferentes, seminal vesicles, and prostate. The sympathetic nervous system, therefore, causes contraction of the internal urethral sphincter and internal anal sphincter, inhibiting urination and defecation, respectively. The sympathetic nervous system has an important role in producing contractions that move sperm and secretions through the male genital ducts during ejaculation. The parasympathetic nervous system produces contraction of the detrusor muscle of the bladder wall and inhibits the internal urethral sphincter, stimulating micturition. It stimulates peristalsis in the distal portion of the digestive tract and inhibits the internal anal sphincter, stimulating defecation. Uncharacteristically, the parasympathetic system also acts on blood vessels of erectile tissues through the cavernous nerves, promoting vasodilation and producing erection of the penis in the male.

General visceral afferent (GVA) nerve fibers accompany sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers within the pelvic nerve plexuses. As elsewhere in the body, nerve impulses involved in visceral reflexes are carried by GVA fibers traveling with parasympathetic fibers.

The transmission of pain from pelvic viscera is more complicated than it is from thoracic and abdominal viscera. General visceral afferent fibers carrying pain impulses from pelvic viscera travel different pathways depending on the location of the pelvic organ that they are innervating. In general, if a pelvic organ is located above the inferior limit of the peritoneum or is in contact with peritoneum (pelvic pain line), the GVA fibers carrying pain from it accompany sympathetic fibers toward the spinal cord, just as do GVA fibers carrying pain from thoracic and abdominal organs. Therefore, parts of visceral organs that invaginate the peritoneal sac from below (e.g., the fundus and body of the uterus) send visceral pain to the spinal cord via GVA fibers accompanying sympathetic fibers. If a pelvic organ is located below the inferior limit of the peritoneum and is not in contact with it, the GVA fibers carrying pain accompany parasympathetic fibers of the pelvic splanchnic nerves to the spinal cord. For example, pain from the superior part of the anal canal (above the pectinate line), which lies inferior to the peritoneal sac and is not in contact with it, is carried by GVA fibers that accompany pelvic splanchnic nerves and have cell bodies within the dorsal root ganglia of spinal nerves S2-4.

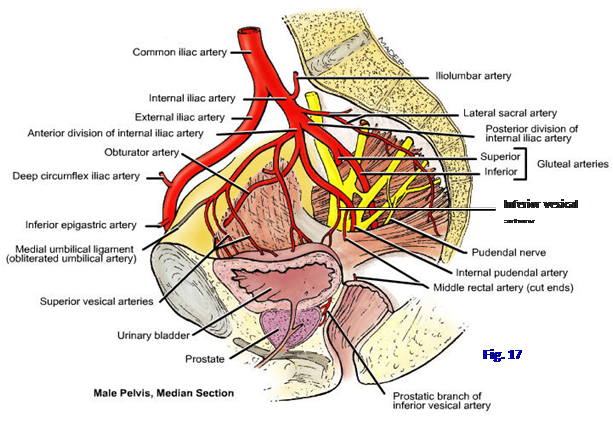

The major blood supply of the pelvis is from the right and left internal iliac arteries, which also send large branches into the gluteal region (G11 3.19, 3.20A, Tables 3.3 [pp. 212-213], 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.20, 3.27A, 3.38, 3.39A; N257, 316, 378, 380, 382, 383). Smaller contributions come from the unpaired median sacral and superior rectal arteries. In the female, the ovarian arteries also enter the pelvis.

Each internal iliac artery (clinically called the “hypogastric artery”) arises from the bifurcation of the common iliac artery at the level of the L5 intervertebral disc (Fig. 17; G11 3.19, Table 3.3 [pp. 212-213]; G12 3.20, 3.27A, 3.39A; N257, 382). It descends anterior to the sacroiliac joint, from which it is separated by the internal iliac vein. At the superior border of the greater sciatic foramen, the internal iliac artery divides into anterior and posterior trunks (divisions) (N382). The branches of each trunk are variable, but a classic branching pattern is described as a reference (and testing) point.

The posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery typically has three branches—iliolumbar, lateral sacral, and superior gluteal—but may also include the inferior gluteal artery (Fig. 17; N316, 382, 383). The iliolumbar artery ascends superolaterally, leaving the lesser pelvis, to divide into lumbar and iliac branches. The lumbar branch continues ascending to supply the psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles. The iliac branch courses laterally into the iliac fossa to supply the iliacus muscle.

The lateral sacral artery may arise as a single branch that divides into superior and inferior lateral sacral arteries or as two separate arteries (Fig. 17; G11 3.10, 3.24, Table 3.3; G12 3.12, 3.16, 3.27A; N257, 316, 382). The lateral sacral arteries descend medially anterior to the anterior sacral foramina, giving off branches that enter the foramina. These branches supply the meninges and other structures within the sacral canal and some continue through the posterior sacral foramina to supply the erector spinae and overlying skin and fascia.

The superior gluteal artery is the largest branch of the posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery (Fig. 17; G11 3.10, 3.19A, 3.24, 5.24, 5.25, Table 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.12, 3.16, 3.39A, 5.26A, 5.27A; N257, 316, 382). It usually passes between the lumbosacral trunk and anterior ramus of S1 to leave the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle. As anatomical variations it may pass above the lumbosacral trunk or between S1 and S2. The superior gluteal artery supplies the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and upper half of the gluteus maximus muscles.

The branches of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery are mainly visceral, supplying pelvic and perineal organs. The umbilical artery is the first branch and passes along the lateral pelvic wall before ascending in the anterior abdominal wall toward the umbilicus (Fig. 17; G11 2.18, 3.19B, Tables 3.3 [pp. 212-213], 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.27A, 3.28A, 3.39A; N257, 316, 380, 382, 383). Before birth, it returns deoxygenated blood from the fetus through the umbilical cord to the placenta. At birth the part of the artery distal to the bladder closes off to become the medial umbilical ligament, and a fold of peritoneum is raised over it as the medial umbilical fold (G12 2.17; N247, 380). The patent part of the umbilical artery gives off superior vesical arteries to the superior aspect of the urinary bladder.

The obturator artery usually arises from the anterior trunk close to the umbilical artery (Fig. 17). It passes anteriorly across the obturator internus fascia on the lateral wall of the pelvis to exit the pelvis through the obturator canal. The obturator artery provides small branches to the upper portion of the medial compartment of the thigh. The pubic branch of the obturator artery arises just proximal to its entrance into the obturator canal and ascends across the superior ramus of the pubis to anastomose with the pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery (G12 3.28C). An important variation is that the pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery may form an aberrant or accessory obturator artery (labeled an “aberrant” or “accessory” artery depending on whether or not it is the only obturator artery or a supplemental artery, respectively). It descends across the pelvic brim to the obturator canal (G11 3.19B, 3.20B; G12 3.28A-B [labeled “Anomalous”]; N 378, 382). An aberrant obturator artery runs close to the femoral ring (N253) and is in danger during the surgical repair of a femoral hernia.

The inferior vesical artery is present only in males (Fig. 17; G11 3.19B; G12 3.27A, 3.28B, Table 3.4 [p. 225]; N378, 383). It may arise independently from the internal iliac artery or in common with the middle rectal artery. The inferior vesical artery passes to the fundus (base) of the bladder, supplying it along with the seminal vesicles, prostate, and inferior part of the ureter. The artery to the ductus deferens usually arises from the inferior vesical artery (G11 3.19B; G12 3.27A, Table 3.4 [p. 225]; N378, 381) but may arise from a superior vesical artery. The vaginal artery of the female corresponds to the inferior vesical artery of the male. (Note: some figures of female cadavers in Netter’s have an artery mistakenly labeled as “Inferior vesical artery.”)

The middle rectal artery may branch separately from the internal iliac artery or may arise in common with the internal pudendal or the inferior vesical artery (Fig. 17; G11 3.19, Table 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.20, 3.28A, 3.39A; N378, 383). It helps to supply the rectum and anal canal, anastomosing with the superior rectal artery (inferior mesenteric) and inferior rectal artery (internal pudendal) (G11 3.10B; G12 3.17A; N288, 378).

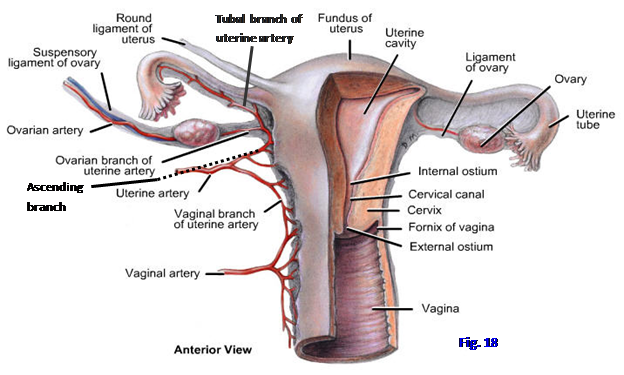

The uterine artery typically arises as a separate branch of the internal iliac artery in the female (Fig. 18; G11 3.29, 3.31, 3.35, Table 3.5 [pp. 234-235]; G12 3.35C, 3.33A, 3.34A, 3.39A; N345, 380, 382, 384 [Note: in Figs. 345, 380, and 382 ignore the vessel incorrectly labeled as the “Inferior vesical artery”). The uterine artery courses anteriorly and medially within the transverse cervical ligament at the base of the broad ligament to reach the cervix. The uterine artery enlarges significantly during pregnancy. Near the lateral fornix of the vagina the uterine artery passes directly superior to the ureter (easily remembered as “water passes under the bridge”) (G11 3.29, 3.31; G12 3.33A, 3.35C, 3.37; N380, 384). This relationship is important because the ureter is in danger of being ligated or cut during surgical removal of the uterus (hysterectomy). It also means that the ureter may be obstructed in advanced cancer of the cervix. Near the cervix the uterine artery divides into a larger ascending branch to the body and fundus of the uterus and a vaginal branch to the cervix and vagina (Fig. 18). The ascending branch of the uterine artery contributes to the blood supply of the uterine tube and the ovary.

The vaginal artery of females corresponds to the inferior vesical artery of males. It usually branches from the uterine artery and anastomoses with the vaginal branch of the uterine artery (Fig. 18; G11 3.31, 3.35; G12 3.33A, 3.34A; N 380, 382, 384). The vaginal artery supplies the vagina and the posteroinferior parts of the urinary bladder and the urethra.

The internal pudendal artery usually is the smaller terminal branch of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery. It descends inferolaterally between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles to traverse the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis (Fig. 17; G11 3.24 [Note: the labels for the levator ani and coccygeus are switched in this figure], 5.25; G12 3.12, 5.27A; N257, 382, 383). The artery follows the pudendal nerve’s short transit through the gluteal region, around the ischial spine and into the lesser sciatic foramen to reach the perineum. The internal pudendal artery is the major blood supply to the perineum.

The inferior gluteal artery is the larger terminal branch of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery. It usually arises from the anterior trunk but may branch from the posterior trunk (Fig. 17; G11 3.19B, 3.24, 5.24, Table 3.3 [pp. 212-213]; G12 3.12, 3.27A, 3.28A, 5.26; N257, 316, 382, 383). The inferior gluteal artery regularly exits the pelvis between the anterior rami of S2 and S3, but it may exit between S1 and S2. It supplies the gluteus maximus and other muscles of the gluteal region and participates in the cruciate anastomosis.

The pelvic organs are largely drained by pelvic veins that correspond to the branches of the internal iliac artery (G11 3.21A; G12 3.27B, 3.39B; N258, 379, 383). These tributaries of the internal iliac veins are formed from pelvic venous plexuses surrounding pelvic viscera (e.g., the rectum, bladder, and prostate). The internal iliac veins join the external iliac veins to form common iliac veins. These in turn unite to form the inferior vena cava. The small median sacral vein is also a tributary of the inferior vena cava or the left common iliac vein near its termination (N258).

Other paths of venous drainage from the pelvis, although smaller, are clinically important in metastatic carcinoma. Venous blood may drain through the lateral sacral veins to the internal vertebral venous plexus, providing a pathway for the spread of pelvic cancer (e.g., prostate cancer) to the vertebral column, spinal cord, and brain. Cancer from the rectum and the anal canal above the pectinate line may drain through the superior rectal and inferior mesenteric veins into the portal system of veins to reach the liver (G11 2.60, 2.61, 3.21B; G12 2.60, 2.61, 3.29; N291, 292, 379).

The pelvic veins are located largely external to the arteries along the pelvic walls and may be involved in pelvic fractures. Fatal hemorrhage may result from torn pelvic veins or/and arteries (e.g., see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1397135/pdf/annsurg00396-0108.pdf ).

1. Retract the bladder, rectum, and in the female the uterus, away from the lateral pelvic wall. Clean the common iliac artery to its bifurcation into the external and internal iliac arteries. You may have to remove the pelvic veins to expose the arteries and sacral plexus. Although we aren’t preserving the pelvic veins, be aware of their potential for fatal hemorrhage in pelvic fractures. Clean the internal iliac artery and find its division into anterior and posterior trunks (Fig. 17). The posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery usually has iliolumbar, lateral sacral, and superior gluteal branches.

2. Trace the iliolumbar artery superiorly from the upper part of the posterior trunk (or occasionally from the internal iliac artery before its division). Find the iliolumbar artery’s division into a lumbar branch that continues ascending and an iliac branch that passes laterally into the iliacus muscle. The lateral sacral artery descends along the sacrum medial to the emerging anterior rami of sacral spinal nerves. The lateral sacral artery may arise as superior and inferior arteries or as a single stem that branches.

3. The superior gluteal artery is the largest branch of the posterior trunk. It leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle. Typically the superior gluteal artery passes between the lumbosacral trunk and the anterior ramus of S1, but it sometimes passes superior to the lumbosacral trunk. Clean these structures.

4. The inferior gluteal artery is described as arising from the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery, but it frequently arises from the posterior trunk. It exits the pelvis below the piriformis after passing between (usually) the anterior rami of S2 and S3. From which trunk does the inferior gluteal artery branch in this cadaver?

5. Clean the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery. The umbilical artery is the first branch. Find two or three small superior vesical arteries leaving the umbilical artery to supply the upper portion of the bladder. Trace the fibrous continuation of the umbilical artery, the medial umbilical ligament, into the anterior abdominal wall. The fold of peritoneum raised over the ligament is the medial umbilical fold.

6. Locate the obturator artery running forward along the lateral wall of the lesser pelvis with the obturator nerve. As the artery approaches the obturator canal, look for the small pubic branch ascending to anastomose with the pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery. An important variation is that the latter gives rise to a relatively large aberrant or accessory obturator artery, which is in danger during femoral hernia surgery (G11 3.19B, 3.20B; G12 3.28A-B). Is an aberrant obturator artery present in this cadaver?

7. Follow the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery inferiorly to locate the inferior gluteal and internal pudendal arteries. The inferior gluteal artery may have been seen as a branch of the posterior trunk. If it branches from the anterior trunk, follow it to where it passes between the anterior rami of S2 and S3 (sometimes S1 and S2) to exit the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle. The next artery down, also leaving the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, is the internal pudendal artery. It passes between the coccygeus and piriformis muscles.

8. IN MALE CADAVERS, identify and clean the inferior vesical and middle rectal arteries coursing medially. They frequently arise from a common stem. Alternatively, the inferior vesical artery may arise independently from the internal iliac artery. Trace it toward the fundus of the bladder and the prostate. Find the middle rectal artery passing to the rectum. It’s necessary to clean these arteries all of the way to the organ that they supply to accurately identify them.

9.IN FEMALE CADAVERS, clean the uterine artery coursing toward the cervix of the uterus. Verify that the artery crosses above the ureter just lateral to the cervix in the base of the broad ligament of the uterus. Remember that at this point, the uterine artery is located within the uppermost part of the transverse cervical ligament. Find the vaginal artery, which typically branches from the uterine artery. Look for the vaginal artery’s anastomosis with the vaginal branch of the uterine artery, which descends to meet it. The vaginal artery corresponds to the inferior vesical artery in males. (Note: in Netter’s Atlas ignore the artery labeled “Inferior vesical artery” in figures of the female pelvis.)

10. If the right lower extremity was removed in this cadaver, find the superior rectal artery descending from the inferior mesenteric artery and dividing into branches to supply the rectum. Remember that it anastomoses with the middle and inferior rectal arteries. The anastomoses of the corresponding superior rectal vein with the middle and inferior rectal veins is a portacaval anastomosis important in portal hypertension (e.g., due to cirrhosis of the liver) (G11 2.61, 3.21B; G12 2.61, 3.27B; N291, 292, 379).

NERVES OF THE PELVIS

11. Now study the nerves of the pelvis. Finish cleaning the piriformis muscle on the pelvic surface of the sacrum. Identify the lumbosacral trunk descending across the ala of the sacrum to enter the lesser pelvis. Find where it meets the anterior ramus of spinal nerve S1. The superior gluteal artery probably passes between the lumbosacral trunk and S1 but may pass superior to the lumbosacral trunk. Clean the anterior rami of S2, S3, and S4.

12. Many of the smaller branches of the sacral plexus are difficult to identify at their origins, but clean the large sciatic nerve (L4-S3). It exits the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle. Find the superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1) as the only nerve leaving the pelvis above the piriformis.

13. Clean the obturator nerve (L2-4) descending from the lumbar plexus and passing along the lateral wall of the pelvis above the obturator artery and vein. The obturator nerve exits the lesser pelvis through the obturator canal, a small anterior-superior gap in the obturator membrane, to supply muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh. The obturator membrane is hidden from medial view by the obturator internus muscle, which covers the membrane and takes partial origin from it.

14. Trace the lumbar sympathetic trunk descending toward the pelvis on the intact side of the cadaver. It becomes the sacral sympathetic trunk at the pelvic brim. If the midline saw cut was slightly off center, look for the fusion of the two sympathetic trunks in the small ganglion impar in the larger half of the pelvis (G11 3.26; G12 2.76 [unlabeled]). Dissect a gray ramus communicans passing from each sacral sympathetic ganglion to the anterior ramus of a sacral spinal nerve (G11 3.24; G12 3.12). Be aware that the gray rami communicantes carry postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers for distribution to the smooth muscle and glands of the lower extremity.

15. Find the remaining half of the superior hypogastric plexus just below the aortic bifurcation on the intact side of the body. Remember that it is the continuation of the intermesenteric plexus (part of the aortic plexus). Trace the hypogastric nerve of the same side into the pelvis, where it joins the inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexus lateral to the pelvic organs (G11 3.36B, 3.37B, 3.39; G12 2.76, 3.31A-B, 3.43; N319, 389, 390, 392). Clean the small pelvic splanchnic nerves carrying preganglionic parasympathetic fibers from S2-4 to the inferior hypogastric plexus. Be aware that there are sub-plexuses associated with individual pelvic organs (e.g., rectal and vesical plexuses [N390]), but don’t attempt to identify them.

WALLS AND FLOOR OF THE PELVIS

16. Again study the piriformis muscle arising from the sacrum near the pelvic sacral foramina. Anterior rami of sacral spinal nerves pass laterally anterior to, and in some cases through the origin of, the piriformis (G11 3.4, 3.5; G12 3.11, 3.12; N392, 487). Follow the piriformis to the greater sciatic foramen.

17. Clean the exposed part of the obturator internus muscle just below the pelvic brim. The obturator internus takes origin from the obturator membrane and the bony margins of the obturator foramen with its fibers converging posteriorly to pass through the lesser sciatic foramen. The fascia covering it is obturator fascia. Identify a thickening of the obturator fascia along a line running posteriorly from the body of the pubis to the ischial spine (G11 3.4, 3.13A & C; Table 3.2 [p. 193]; G12 3.9, 3.10, 3.22A & C; N 337, 338, 340). This is the tendinous arch of the levator ani muscle (arcus tendineus). The muscle descending medially and somewhat posteriorly from it is the thin iliococcygeus portion of the levator ani. The iliococcygeus may be largely aponeurotic.

18. Anterior to the iliococcygeus identify the pubococcygeus taking origin from the posterior surface of the body of the pubis. The third component of the levator ani, the puborectalis, typically isn’t visible from a superior view (despite incorrectly labeled figures in many anatomy books). Instead look for the puborectalis as the sagittally sectioned muscle just posterior to the anorectal flexure (G11 3.6A, 3.7A; G12 3.14A, 3.15A; N 337, 371). Remember that the levator ani is covered by superior and inferior fasciae, but don’t attempt to demonstrate these.

19. Find the coccygeus muscle located between the iliococcygeus and the piriformis muscles. The coccygeus joins the levator ani to form the pelvic diaphragm. Palpate the sacrospinous ligament through the overlying coccygeus muscle.

20. The funnel-shaped pelvic diaphragm supports pelvic organs, assists in maintaining urinary and fecal continence, and separates the pelvis from the perineum, which will be studied during the next period. XXX

The illustrations in this dissection guide are used with permission from Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 2005, by Richard Drake, Wayne Vogel, and Adam Mitchell, Elsevier Inc., Philadelphia; and from Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 11E, 2005, Anne Agur and Arthur Dalley II, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.